Few people would have imagined the state of the world in 2020. As of this writing, over 300,000 lives have been lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic, worldwide. Tens of millions of jobs have disappeared. Hundreds of millions of people are suddenly working remotely. Billions are confined to their homes. A disruption of this magnitude is going to leave a mark on civilisation. While everyone is understandably focused upon its immediate effects, the COVID-19 pandemic will have social and economic consequences that are felt for generations to come.

For public transport, the immediate effects have been catastrophic. There have been 80%-90% reductions in ridership and farebox revenue, and sudden redesigns of networks and service offerings in the face of staff shortages and funding shortfalls. This, too, will not be a short-term disruption. The cascading consequences of the pandemic will cause chaos in the transport sector for years — although the exact nature of that chaos is currently impossible to predict.

To predict the future, one would have to answer many of the following questions: How many people will die? Will jobs come bouncing back, or will mass unemployment persist? Will people soon forget their fear of shared spaces, or will mass transit be shunned for a generation? Will transport budgets be starved by economic recession, or swollen by stimulus spending? Will people choose to live in urban centres with ample accommodations for pedestrians or cyclists, or will they retreat to suburbs and private cars? Will people still commute to work in the same way, or will employers stagger commute times to reduce crowding, or will there be a shift to working from home? Will the recent explosion of micromobility schemes — cycle and scooter sharing — resume their growth, or will germophobia nip that burgeoning industry in the bud? Will other innovative new transport technologies fill the gaps, or will cultural conservatism lead to only tried-and-true technologies being trusted? Will a suddenly-raised mass consciousness of existential threats extend to real action on climate change — with all the implications for transport and land-use which that implies — or will economic stagnation kill off any talk of Green New Deals and transport electrification?

For transport operators and others in the sector, the answer to many of these questions could reveal existential threats — or opportunities. And right now, all these questions have the same simple answer: nobody knows. So what can transport operators and planners do in the face of such an uncertain future?

In fact we don’t need to be rudderless in this time of flux. There are tools and techniques which can help us navigate through this crisis and beyond — and we may yet find opportunities hidden within, as we adapt to the new reality that the pandemic is illuminating for us all.

The future is not written: rethinking forecasting

An immediate casualty of the pandemic should be the transport sector’s traditional approach to travel-demand forecasting.

Traditional travel-demand forecasts often extend for years or decades into the future, predicting who will live where, and how they’ll commute to work, and make other travel movements. Based on historic travel data, the model predicts how people will value their time, and their biases for or against various modes. Calibrated and validated travel-demand forecasts are expensive and time-consuming to produce. In some jurisdictions I’ve worked in, the local authority would create an official model that was updated once every decade. (In one instance, while working on a transport project where the official model was too outdated and low-resolution to be useable, my team had to produce a new, project-specific model. This ultimately required nearly a year of work, employing almost 1,000 people at its peak — surveyors counting vehicles on the street, interviewing thousands of randomly-sampled commuters, etc. It was not a cheap or agile undertaking.)

Travel-demand forecasts can be useful tools, but they can also be deeply problematic, even at the best of times. These are not the best of times, and conventional forecasting techniques have been rendered all but useless. Before looking at what can work instead, let’s consider why conventional forecasting isn’t working now, and won’t work in the future.

Forecasting has three primary dangers:

- Hidden biases which obscure strategic possibilities rather than revealing them.

- Failure to consider external factors that can invalidate the model.

- Encouraging the development of fragile, over-optimised strategies.

1. Hidden variables mean hidden biases

Forecasts are, fundamentally, a way of drawing a trend line through past data, and extrapolating that trend into the future. A poor forecast will draw a line through the wrong data to produce meaningless results, whereas a good forecast will identify the underlying root causes of high-level trends, extract trend-lines from those root causes, and then extrapolate the high-level trend, projecting it into the future with appropriate error bars and caveats. This process has a scientific aura, since it is data-driven and quantitative. And it can be predictive and useful. But it is not, in fact, scientific, and there are deep problems with this methodology, even when it works as intended.

One problem is that forecasting gives a sense that the future is more deterministic than it actually is: that the future simply happens, rather than that the future is created.

For example: a forecast might observe that road congestion is increasing, determine that this is driven by an underlying increase in travel-demand, and predict that travel-demand and therefore road congestion will continue to increase in the future. The conclusion inevitably drawn from such a forecast is that road capacity needs to be increased. When that is done, it is often observed that travel-demand does in fact continue to increase, thus validating the forecast. But more often than not, that increase is greater than the additional road capacity, so that the road becomes even more congested than before.

(The predictability of this scenario has led to the myth of “induced demand”: that adding more road capacity will always increase congestion — or, as Lewis Mumford said, “Adding highway lanes to deal with traffic congestion is like loosening your belt to cure obesity”. It’s a well-attested phenomenon — but it is also something of a myth, because of the implication that induced demand is unique to roads. It isn’t. If train tickets were priced the same as road capacity — free — then you’d see induced demand on trains as well. Same goes for chocolate bars, or any other valuable good which is given away for free.)

But what if the road is removed, rather than widened? Surely, because underlying travel-demand is increasing, this means that the congestion would just shift to other roads? As it turns out, this isn’t always the case. Sometimes, removing a road reduces congestions on all roads. Why? Because the identification of travel-demand as a root cause was, in fact, incorrect. There were deeper causes at work. People don’t travel simply for the sake of it: they travel to access work, school, healthcare, recreation, etc. And none of those things are static. Absent a particular road, people may choose to walk to a shop closer to home, rather than to drive to a larger retailer. Or they may choose to move closer to their work, rather than take a longer commute. Or shops and workplaces may move closer to them. Any of these factors would reduce congestion, and none of this would have been considered by the forecasting process, unless it included a feedback loop between travel accessibility and land-use changes as part of its modelling process — which is rarely, if ever, done.

So as you can see: when forecasts work, it isn’t necessarily because they’ve been neutral observers of an inevitable future. They are active participants in their futures: self-fulfilling prophecies, heavily biased towards continuing past trends. They come with the status quo “baked in”. This is problematic because it means that hidden variables in the forecasting process can create unintended biases, constraining the decision-making of planners, operators, and policymakers who rely on the forecast.

At this time of crisis — when decision-making needs to be as broad and perceptive as possible — unintended biases are the last thing that you need to have constraining your strategic possibilities.

But surely one should just try to make forecasts richer and more accurate, yes?

Well, yes, of course, that wouldn’t be a bad thing, per se. Travel-demand forecasting should, for example, consider the reciprocal relationship between changes in the transport network and changes in land-use. But there are deeper issues than the transport network which affect changes in land-use — sociopolitical and cultural issues — and still deeper issues beneath those. Essentially, it’s turtles all the way down, which brings us to the next major problem with forecasting: there is no level of resolution at which the model can ever be “right”.

2. Some models are useful, but all models are wrong

Seemingly trivial events can completely wreck even the most carefully-constructed forecast.

Consider that in 2020, every single travel-demand forecast in the entire world has been completely demolished by someone in Wuhan eating an undercooked bat (or so goes the most popular theory for the emergence of the coronavirus). No travel-demand forecast could ever have predicted that singular event which has led to a massive global crisis.

Does this seem extraordinary to you? It’s not. Although the specificities of how and when such “Black Swan” events will occur can’t be predicted, that they will occur is, ultimately, guaranteed. History often pivots on such trivial, seemingly innocuous fulcrums. Consider climate change and terrorism, which are surely two of the defining issues of the twenty-first century. Nobody would deny that if Al Gore had been president at the turn of the century, the world’s relationship to both these issues would be profoundly different, for better or worse. So why wasn’t he president? Not because he got fewer votes — he received half a million more votes than Bush; any incautious forecaster would have called him the winner, and many did. But reality didn’t cooperate. A handful of flakey hole-punch machines in some voting booths in Florida led to a cascade of unpredictable consequences, ultimately handing the election to George Bush via a Supreme Court decision, and setting the twenty-first century on an entirely different course.

Undercooked bats. Floridian hole-punch machines. The anecdotes are endless. Most people find it difficult to accept how fickle these turns of history can be. They construct retrospective narratives which imbue history with a sense of rational continuity, making the sequence of (say) Clinton to Bush to Obama to Trump sound like inevitable swings of some history-inscribing pendulum. Sometimes, of course, history does have momentum and follow predictable trajectories — and when that is the case, forecasting can work. But that isn’t guaranteed. At other times, history takes a sharply different path simply because a butterfly flapped its wings and set the dominos toppling over. That’s when forecasting fails.

Right now we’re living in a world which has been forever changed by the Coronavirus, which no forecast could have predicted. So can we use forecasting to find our way to a better world? If those forecasts assume continuity with the past, then no, we can’t, because that’s a fundamentally flawed assumption. But if forecasts are able to take into account the potential discontinuities of the future, then they can still be very useful.

There are a lot of potential discontinuities in our future — many fulcrums upon which history will unpredictably pivot. Will the funding environment be one of austerity or stimulus? This depends on the political philosophies of a handful of policymakers — and those philosophies have been shifting rapidly, sometimes unexpectedly, in the face of this unprecedented challenge. Will society re-embrace socialisation and shared spaces as we emerge from lockdown, or will there be a long-lasting aversion to close contact with strangers? This could depend on many different factors, including which memes gain momentum on Twitter and how they’re amplified by the mass media.

In short: this could head in almost any direction. The truth is that there are many possible futures branching out from this moment, some of them very different from others, and none of them will be the straightforward continuation of past trends. Accepting this multiplicitous reality is the first step to successfully navigating it.

3. Over-optimising for singular scenarios

This brings us to the final problem with conventional forecasting: because it paints a singular picture of the future, transport agencies often respond by optimising their strategies around that “most likely” future scenario — and that one future only. This can be very efficient if the future unfolds as the forecast predicted. But when the future unfolds differently, such optimisations can be dangerously brittle, since all of the eggs have been placed into a single strategic basket. Efficiency, taken to extremes, can be the opposite of resilience. And resilience is what’s needed the most in these uncertain times.

So, how do we navigate multiple possible futures to create resilient strategies? By using our imaginations.

No quantitatively-derived forecast could have predicted when, where, and how the coronavirus pandemic would happen. But “unpredictable” isn’t the same thing as “unimaginable”. Scenario planners, futurists, and even science-fiction writers have been imagining pandemics and other “black swan” scenarios for generations, using their story-telling abilities to construct rich, plausible narratives — not about what will happen, but about what could happen. Because these are narrative exercises rather than quantitative exercises, they can include whatever level of detail is needed to understand the relevant causal forces — social, political, psychological, biological, and so forth — overcoming the inability of traditional forecasting to capture such factors. These narratives can help create better understanding of how to survive and thrive in a variety of possible futures, without actually being predictive.

Living with multiple possible futures

Since the 1970s, there has been an evolving practice within management consulting known as “Scenario Planning”. The key objective of this practice is to break organisations of their habit of thinking about singular futures, to help them explore the “possibility space” of multiple divergent futures, and to formulate more resilient strategies that can cope with any possible future. This practice has always been relevant to transport planners, and in these uncertain times, it’s more relevant than ever.

The purpose of scenario planning is not to predict what will happen — impossible in uncertain times such as these — but rather to get a better handle on what plausibly could happen. Once you’ve done that, you can begin to create resilient strategies: either robust enough to survive many different futures, or else agile enough to pivot depending on which future you find yourself in.

Let’s look at how that might work in practice.

First, it’s not possible for a consultant scenario planner to walk up and simply tell you what all the different possible futures might look like. For one thing, no consultant will understand the particulars of your organisation, your stakeholders, and your overall domain as well as you do. For another thing: even if a consultant could simply map out possible futures for you, you wouldn’t buy into them. Why those particular futures, rather than others? Decision-makers need to be able to sift through future scenarios themselves, in order to create enough buy-in to begin developing strategies for them.

In a corporation, “decision makers” generally implies a group of board or executive-level professionals. But in transport, it’s different. In this context, who isn’t a decision maker? The executive who authorises a new service is a decision maker, of course — but so is the passenger who decides to ride that service (or not). Therefore, in our sector, it’s important to engage with as many different perspectives as possible, in order to better understand the full breadth of possible futures — as well as the full breadth of current understandings, which might already be highly divergent. These futures should be sourced from as many stakeholders as are relevant to you: bus drivers and bankers, politicians and pensioners, commuters and college students, accountants and activists, technologists and technophobes. All individuals will have something unique to contribute. Put them together, and you’ll start to get a more accurate understanding of the breadth of possibilities.

To acquire this kind of understanding, you’ll need new, creative ways to communicate and engage your peers, community, and colleagues. Then to convert this understanding into effective action, you’ll need new practices, tools, and ways of thinking. Note that these aren’t separate steps: action should of course derive from understanding, but nothing creates understanding better than taking action, and learning from it. Therefore, this should be thought of as a tightly-coupled feedback loop: understanding leading to action, leading to better understanding, and better action. The more rapidly and frequently you can do this, the better your outcomes will be.

But how do you “put together” a diverse range of future scenarios, many of which will be mutually exclusive? Scenario planners have developed a traditional methodology which I’ll outline below, but the important thing is that you construct at least four plausible, richly detailed scenarios. (Three is too few: these will inevitably become the “good”, “bad”, and “middle-of-the-road” scenarios, and eventually our bias against discontinuities will cause only the middle scenario to be taken seriously).

Typically, scenario planners gather a range of stories, then identify the two most important independent factors within those stories. To identify these factors, one should look for root-causes which substantially drive the outcomes in their scenarios, and about which there is significant uncertainty or disagreement. (Note how starkly different this is from traditional forecasting methodologies, which seeks to understand the factors we can be most certain about, and then makes extrapolations based upon those. Scenario planning explicitly seeks to extrapolate from uncertainty).

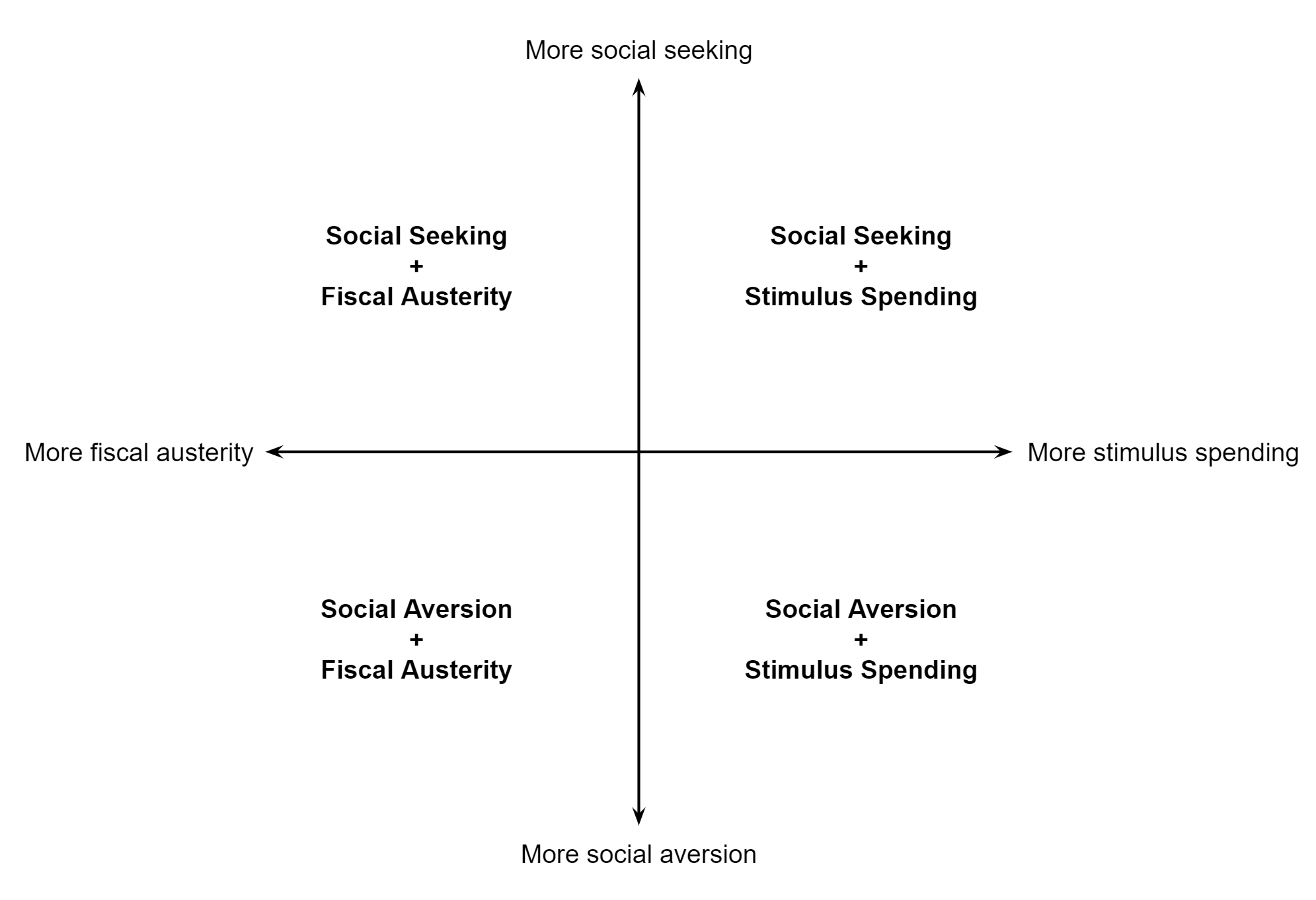

For a local authority looking at post-pandemic scenarios, those root causes might be something like “economic climate” and “social attitudes”. (These are just examples for the sake of demonstration; your own stakeholders might identify different root-causes that are more applicable to your context.) Each of these root-causes is then put on an axis: the “economic climate” axis might range from “fiscal austerity” to “major stimulus spending” depending on the government response to the forthcoming recession, whereas the “social attitudes” axis might range from “social aversion” to “social seeking”, as people either shun socialisation or dramatically re-embrace it.

These two axes produce four quadrants:

These four scenarios are intended to be as qualitatively different as possible — not “bad” or “good” (although from the local authority’s perspective, “stimulus spending” probably looks rather better than “fiscal austerity”). These scenarios should then be made as rich and multifaceted as possible, by compositing elements from the various stakeholder-sourced stories. An enriched set of scenarios might look something like this:

-

Stimulus Spending + Social Seeking: People are desperate to return to the pubs and theatres and offices and so forth, putting enormous stress on the roads and public transport systems. At the same time, the government is pumping money into infrastructure construction, to help stimulate job creation. The major problem you need to solve is decongesting high-volume corridors into city centres, while the major opportunity is to grab a slice of that stimulus spending. You’d better start planning new mass-transit systems in a hurry — the more ambitious the better.

-

Stimulus Spending + Social Aversion: The government wants to pump money into job creation through new infrastructure, but nobody wants to get on a bus or a train anymore. Also, city centres are being shunned as people work from home and shop online, although nearby neighbourhood centres are still attracting some travel-demand. Mass transit won’t suit rider preferences or demand patterns, and greatly increased road-building would destroy those neighbourhood centres that are still active. So, what to do? Time to start planning Personal Rapid Transit systems, autonomous taxi fleets, elevated cycle highways, and other kinds of transport systems which can cater to socially-distanced journeys — in addition to other public-realm improvements for pedestrians. To seize this opportunity (and your slice of the stimulus), you’ll need to do this quickly.

-

Fiscal Austerity + Social Aversion: People are shunning mass transit and city centres, and the government is reducing subsidies for public transport systems. We’ll need to get creative. Building expensive new infrastructure is probably off the table, but cycling and walking can be encouraged at minimal cost, by blocking off lanes and roads to accommodate greater traffic flows with enhanced social distancing. You need to plan how to do this without impacting road-based services too severely. Plus, maybe there are some new personal autonomous vehicle technologies that can be self-financing — if so, then you’ll need to have strong public/private collaborations in order to deploy those systems at minimum cost to the public purse.

-

Fiscal Austerity + Social Seeking: Existing mass-transit systems see a resurgence of passenger demand, at the same time as a withdrawal of government subsidies that have hitherto been needed for operations. How can the system be optimised to produce higher farebox returns? Are there non-farebox revenue sources that can be tapped, perhaps through commercial partnerships with private fleet operators, or via real-estate value capture? Low-cost pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure would be a useful complement to public transport — increasing ridership by facilitating better access — or an alternative to public transport in case it can’t be maintained.

Strategising for an uncertain future

From these scenarios, we can see several patterns emerging. What we are looking for is to develop strategies that are either “robust” or “agile”. A “robust” strategy is one that works reasonably well in all four quadrants, whereas an “agile” strategy is one that can rapidly be adapted or adopted depending upon which future one finds oneself in. Some strategies we might develop:

-

There is no quadrant in which better cyclist and pedestrian infrastructure wouldn’t be beneficial — although the exact nature of that infrastructure will depend on the economic climate. So planning for more cycling and pedestrianisation is a “robust” strategy; we’ll need to develop better ways to do that.

-

We don’t know whether or not we’ll be able to deploy major new transport infrastructure projects. If we are, then we’ll need to be able to do so quickly. Traditionally, major new transport schemes can spend anywhere from 5 to 15 years getting “shovel ready”; we may need to greatly accelerate that schedule in order to grab a slice of the stimulus funding. Here, we’ll need to adopt an “agile” strategy, preparing to rapidly plan and build new infrastructure schemes, without investing too much into that approach until we’re certain that we’re heading into a future which enables us to do that.

-

In the “austerity” scenarios, careful coordination with third-party organisations, both public and private, will be essential to maximise the efficiency and continuity of services. When public transport journeys are arbitrarily broken up between jurisdictions, agencies or operators, this inconveniences travellers and reduces ridership, while increasing costs for operators. Better coordination would be a win/win proposition — nice to have in any scenario, but critical in the austerity scenarios. This is another “robust” strategy.

-

In the “social aversion” scenarios, conventional mass transit loses much of its viability. Besides taking steps to facilitate cycling and walking, it may be essential to pursue new forms of public transport — autonomous taxis and Personal Rapid Transit systems — which use smaller vehicles and cater to individual journeys. Actually, there is likely to be some application of these technologies in all quadrants, but how they are applied will depend on where you are on the “social attitudes” axis. If on the “social seeking” end of the spectrum, then small-vehicle public transport will be most appropriate as feeder/distributor networks that complement large-vehicle mass transit systems. On the “social aversion” end of the spectrum, small-vehicle systems might supplant larger-vehicle systems outright. So these new technologies will need to be pursued on an “agile” basis.

Engineering for uncertainty

The above strategies are, so far, merely that: strategies. Not plans. Moreover, these strategies will need to be continually revised as new information arrives and you find out what kind of future you’re actually moving towards. At some point, these strategies will need to be turned into concrete actions — plans — and obviously plans need to be based on quantified scenarios, not just narrative scenarios. How do you do this?

With travel-demand forecasts — but not as you know them!

Traditional travel-demand forecasting is carefully calibrated and validated against past data, on the assumption that a model that can accurately “predict” the past, will be able to predict the future as well. This assumption of continuity with the past is, as we have seen, never guaranteed — and today it’s less true than ever. Almost all post-COVID scenarios will be predicated upon fundamental breaks with previous trends; this discontinuity is perhaps the only thing that can be reliably predicted. Therefore, going forward, there is much less need for travel-demand forecasts to be calibrated and validated against the past, as there can be no assumption that the past will be predictive of the future.

Removing this requirement means removing the most expensive and time-consuming part of producing travel-demand forecasts. In place of an ultimately futile attempt at “accuracy”, demand-modelling should instead focus on plausibility and coherency: producing forecasts that are quantitatively consistent with the demographics, attitudes, infrastructure and services being represented in any given scenario. Of course as the facts of a scenario are better understood, the demand forecast would need to be continuously updated — with all the derived engineering and benefit/cost calculations continuously updated as well.

This represents a profoundly different approach to demand forecasting. Rather than spending many months attempting to produce a single canonical forecast, demand modellers need to be producing a wide range of forecasts, rapidly and iteratively refining them in response to changes in the understanding of the strategic environment. Other disciplines would need to be able to react just as responsively, updating their detailed plans accordingly.

Is an approach like this even possible? I believe it is.

Embracing a flexible future

Over the past decade, I have been building two companies: Futurescaper and Podaris.

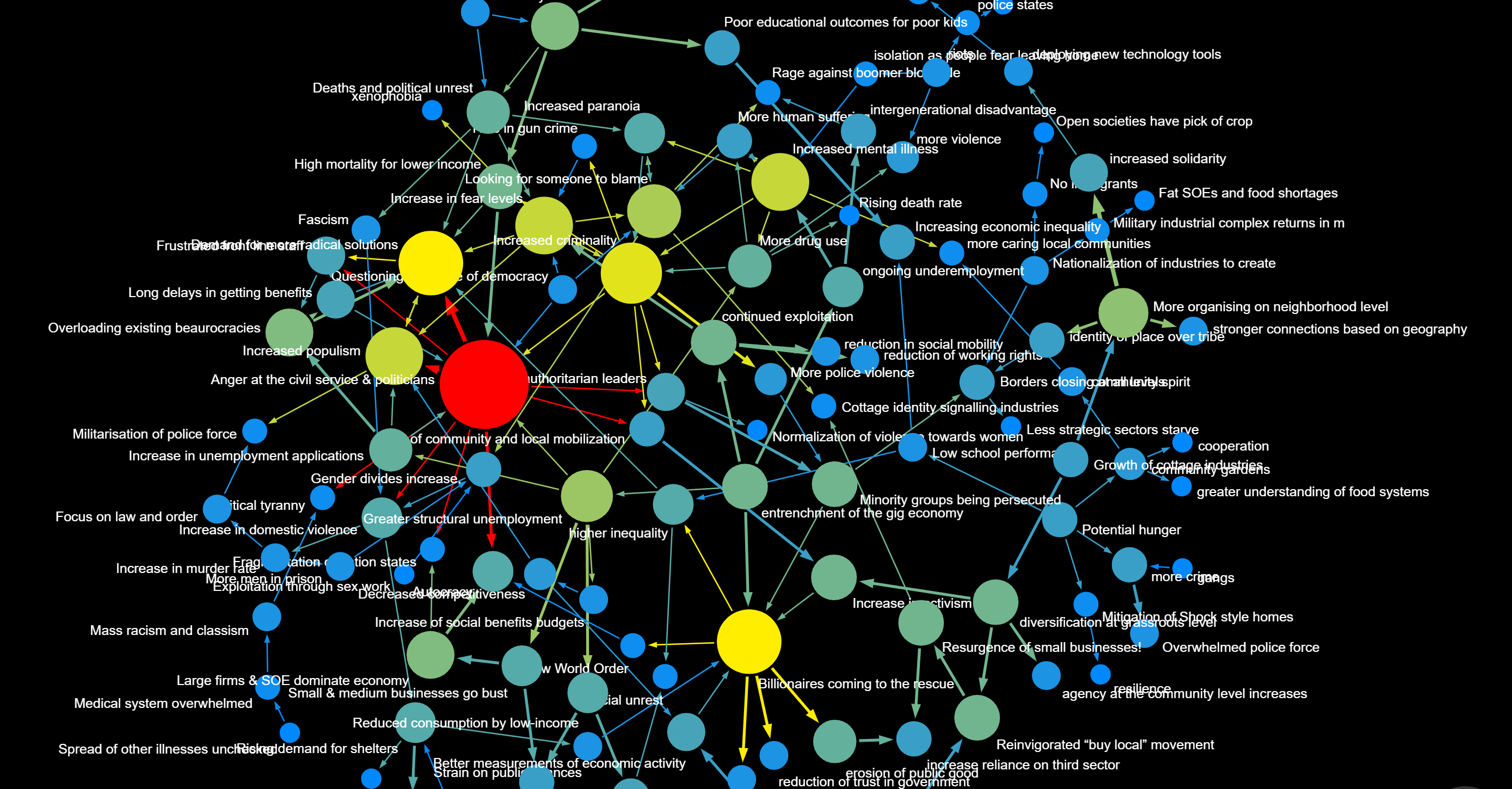

Futurescaper is an online scenario planning platform, which helps organisations collect stories from diverse stakeholder groups, and synthesize them into rich systems maps of the “possibility space” of the future. It has mostly been used by various public sector and non-governmental organisations, including the OECD, United Nations, and various intelligence agencies, but its first-ever project was on the future of transport in Stockholm, synthesizing the views of hundreds of domain experts. One of the main objectives of Futurescaper was to democratise Scenario Planning, using online crowdsourcing techniques to break Scenario Planning out of the boardroom and make it useful for engaging with a much larger group of stakeholders.

A COVID-19 scenario map in Futurescaper

My second company, Podaris, is another online platform — this time, for planning transport infrastructure and services in a highly collaborative fashion. Think: Google Docs, but for planning transport systems. Podaris provides a collaborative parametric whiteboard on which planners can rapidly bounce ideas off of one another, rapidly analysing the capabilities and limitations of different proposals. It includes tools for high-level system design, scheduling, civil engineering, and demand modelling; it also includes non-technical interfaces that can be used to engage with non-expert stakeholders.

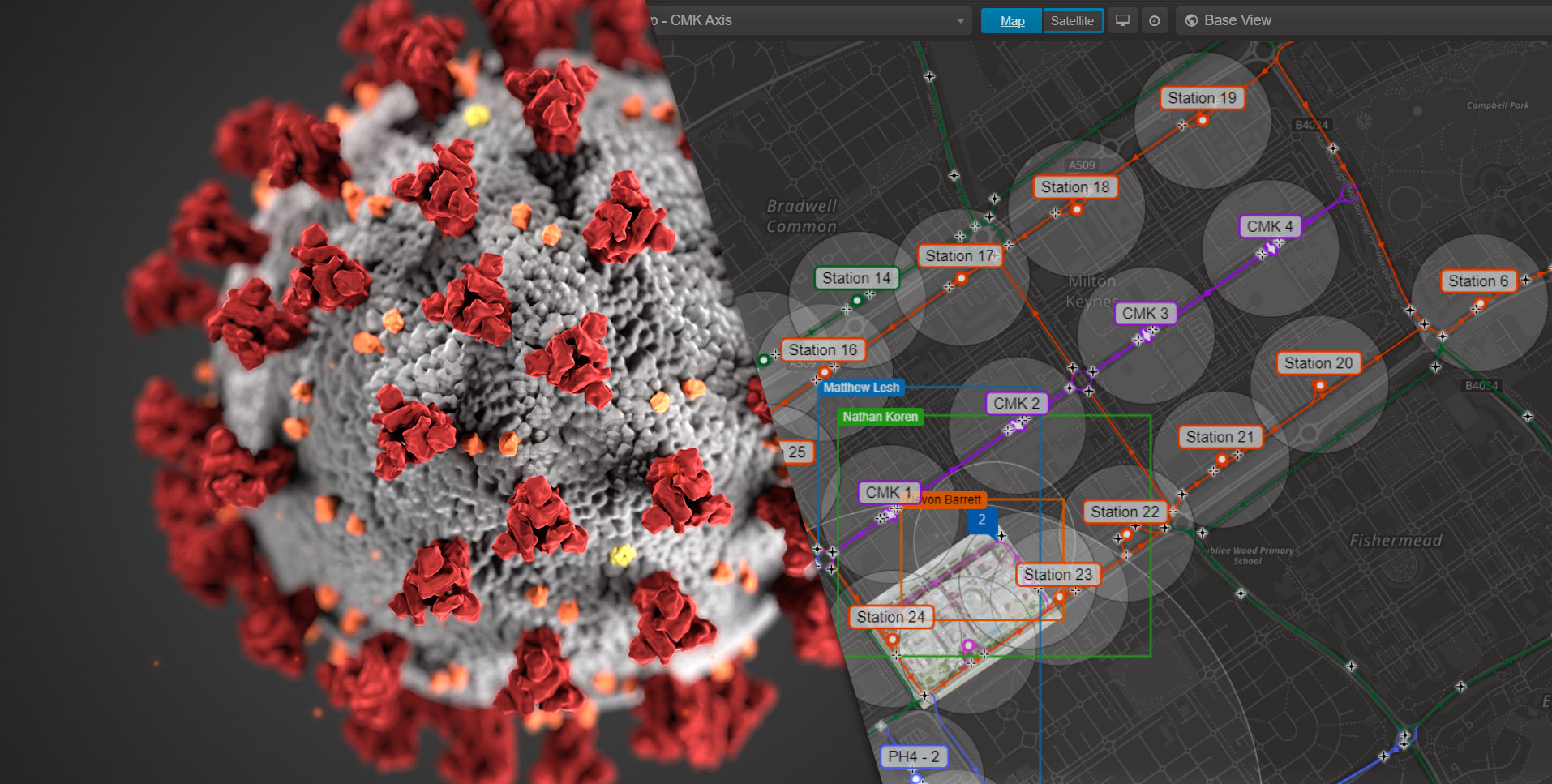

Collaboratively planning an innovative transport network

Although Podaris wasn’t specifically created to facilitate Scenario Planning, its rapid-modelling capabilities make it possible to collaboratively create sophisticated travel-demand and service offering scenarios in literally minutes, where traditional approaches would take weeks. This makes it possible to create a wide range of scenarios, and to iterate them very rapidly, in a way which would be utterly cost- and time-prohibitive using conventional methodologies. These capabilities — allowing for rapid, explorative, inter-disciplinary and inter-agency collaboration — will be essential enabling tools for navigating through the pandemic, and beyond.

Neither Futurescaper nor Podaris were created with this pandemic in mind, of course. I co-founded them based on a longstanding belief that the world needs to get better at planning for the future — particularly in regards to transport and the built environment, which are my areas of expertise, as well as a personal passion. I felt that traditional forecasting approaches were too restrictive in many different fields, and that within transport planning, the tremendous inertia and siloed ways of working were making projects take far too long to deliver, and were inhibiting much-needed innovations. So I created tools to solve these problems, drawing inspiration from the field of software engineering in particular, where philosophies such as “agile development” and “Kanban” (continuous improvement) — and an ecosystem of tools to make these philosophies concretely achievable — have yielded tremendous benefit.

Of course I wouldn’t claim that Futurescaper or Podaris are the only tool which can enable such a flexible future — encouragingly, there are now many different competitors and complementary technologies emerging, bringing broadly similar philosophies to different types of customers and problems. It’s clear that online, highly-collaborative platforms will be the future of not only transport planning, but of planning for all aspects of the built environment. And not a moment too soon, because this emerging ecosystem will be crucial for addressing the many challenges and opportunities of the pandemic.

Becoming more cognisant of the multiplicity of possible futures — and developing robust or agile plans to successfully navigate these futures — will not just be a way to navigate through the pandemic. It will be a fundamental, long-lasting improvement to the way that transport planning is done. There have always been a multitude of futures to plan for, whether we acknowledged it or not. Similarly, doing this planning via online collaborative platforms — with inter-disciplinary and inter-agency coordination a core part of their functionality — will be a fundamental improvement over the glacially slow and disjointed planning practices of the past.

I’m not saying it will be easy. The next few years undoubtedly will be a difficult time for transport planners — it will be a difficult time for the world as a whole. But it need not be catastrophic. We have the means to navigate this storm, and come out stronger and better on the other side.

Founder and CEO Nathan Koren began his career as an architect in America and India, focusing on mixed-use, sustainable, transit-oriented development. In his subsequent role as a transport planning consultant with expertise in autonomous transport systems, Nathan led feasibility studies in over a dozen countries, becoming a recognised expert in the emerging technology of Automated Transit Networks (ATNs), and frequently lecturing on the subjects of automation, transport innovation, and urban design.

He has most recently worked as a digital entrepreneur, as the technical co-founder of Futurescaper — a collective intelligence system for crowdsourced scenario planning, and the founder of Podaris.